6

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

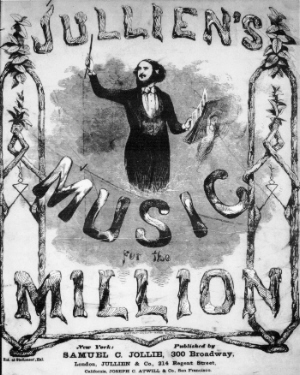

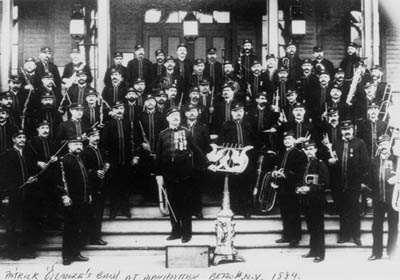

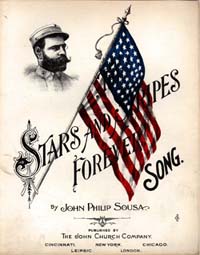

Bands in the 19th century had an enormous impact on the cultural and social lives of the populace of the United States. It was a time when brass bands impacted the war effort perhaps more than any time since the Saracen bands of the Ottoman empire. The golden age of professional bands was ushered in with the music of Patrick Gilmore, John Philip Sousa, and the Italian Giuseppe Creatore, to name a few. Plus, many civic bands were formed to provide performance outlets for the populace in general. It was a rich and colorful time in America's music history. Bands in the United States in the early 19th century were a reflection of European tradition. The instrumentation of the United States Marine Band of 1800 -- 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bassoon, two horns, and a drum -- was influenced by Harmoniemusik and European military practice. Imitation continued to be a factor, especially as European musicians migrated to America. Later, the French Revolution impacted the accepted number of players in bands as well as the type of instruments used. The popularity of Janissary percussion created the need for more wind instruments, especially brass, to balance the ensemble. - Back to Top -THE BRASS BAND MOVEMENTKeyed BrassAt the same time that band instrumentation was going through a dramatic change, the makeup of brass instruments was also undergoing a dramatic evolution. Joseph Haliday of Dublin, Ireland invented and patented the keyed bugle [also known as the Royal Kent bugle] in 1810. Despite the obvious unwieldiness and suspect tone quality, the keyed bugle was a notable step forward in the process of creating brass instruments, which were not limited to the notes available on the overtone series. And with the arrival of the keyed bugle in America about 1815, there began a gradual evolution of American bands to brass bands only. In 1817 the Parisian instrument maker Halary built an entire family of keyed brass instruments that he named ophicleides. Keyed bugles (soprano voices) and ophicleides [large keyed bugle used as a baritone or bass voice, doubled up in the shape of a Russian basshorn] (middle and lower voices) became increasingly popular with American bandsmen in the 1820s-30s. However, the newly invented valved brass gradually made these instruments obsolete, beginning with the ophicleides (1840s), followed by the keyed bugles (1850s). The inevitable decline of the keyed bugle was postponed due to the popularity of soloists such as Ned Kendall.1 Kendall's popularity had its complement in Europe with renowned virtuosos such as Paganini and Liszt and paved the way for the popularity of the great cornetists who followed, beginning with no less than Patrick Gilmore. Valved BrassInventors began experimenting with keyed and valved brass late in the eighteenth century, but the invention of the first successful valve for brass instruments is attributed to Heinrich Stoelzel and Freiderich Bluhmel, two Berlin musicians who patented their design in 1818. Other patents followed in the 1830s: Uhlmann's Vienna twin-piston valve (1830), the Rad-Maschine rotary valve patented by Joseph Riedl in 1832, the Berliner-Pumpen valve patented by Wieprecht and Moritz in Prussia in 1835, and Pèrinet's improved piston valve introduced in 1839.2 Around 1825 in France, an instrument maker (possibly Halary) experimented with adding valves to a small conical and circular coiled instrument known as the cornet simple or cornet de poste. The result became known as the cornet à pistons. The mellow tone quality created by the conical design, coupled with the enhanced technical facility provided by the valves, guaranteed the new cornet popularity as a melodic and solo instrument, which has lasted until today.3 The SaxhornBy 1835, brass bands began to supplant other forms of wind bands in the United States. A conglomeration of brass instruments--including keyed bugles, ophicleides, natural French horns, trumpets, post horns, and trombones--comprised the instrumentation of many of these bands, and quality undoubtedly suffered from lack of intonation, balance, and blend produced by the wide variety of horn lengths and timbre. The curious mixture, while inevitable during this time, was no doubt frustrating to any serious bandmaster trying to lead a band of high quality. In an effort to address this problem, during the 1840s a number of instrument makers in Europe began making sets of chromatic valved bugles designed for all possible voices from bass to soprano. One of these makers, Adolph Sax, had the promotional and business savvy to make his newly manufactured saxhorn the instrument of choice for brass bands. The saxhorn (the universal name for this class of instrument) had much to offer: more consistent tone quality in all registers, better intonation, greater technical facility, and the ability to create a homogeneous sound from the bass to soprano register. The conical design, like that of the cornet, created a warm, mellow sound especially pleasing to the listener. Banding for Good HealthBetween the manufacture of the saxhorn family and his new invention, the saxophone, Adolph Sax had every reason to promote the playing of wind instruments. One example of Sax's self-serving, yet amusing promotional ventures was printed in La France Musicale before eventually finding its way to Boston and Dwight's Journal of Music in 1862:Persons who practice wind instruments, are, in general, distinguished--and anybody can verify the statement--by a broad chest and shoulders, an unequivocal sign of vigor. In the travelling bands that pass through our cities, who has not seen women playing the horn, the cornet, the trumpet, and even the trombone and ophicleide, and noticed that they all enjoyed perfect health, and exhibited a considerable development of the thorax? In an orchestra a curious circumstance can be noticed; and that is the corpulence, the strength which the players of wind instruments exhibit, and the spare frames of the disciples of Paganini. The same may be said, with more reason, of pianists.1 The popularity of the saxhorn was aided by a quintet of English musicians, the Distin family (father and four sons), who performed successful concerts throughout Europe and America. In 1846 Distin & Sons became the official British agent for selling saxhorns. Although the keyed bugle and ophicleide were still used for some time, the cornet and saxhorn became the core instruments for what was rapidly becoming a significant musical movement. Similar to the movement in Great Britain, by the middle of the nineteenth century brass bands were forming in towns throughout the United States. Eventually brass players in America no longer relied on European manufacturers for their instruments. Prior to the Civil War, a number of manufacturers were building quality instruments that rivaled the imports. Boston was the main center of instrument manufacturing, followed by New York, Philadelphia, and several smaller New England towns. No less than Alan Dodworth of the famous Dodworth Band wrote in Dodworth's Brass Band School: "It is conceded by nearly all, that the finest quality of instruments are now made here, by our American manufacturers."4 The music performed by the American brass bands was a mixture of fashionable pieces such as polkas, galops, quadrilles, and waltzes composed by both European and American composers. Patriotic selections and marches by American composers were thrown in for good measure. The most substantial repertoire consisted of light classics such as overtures by Verdi or Rossini. The following lists a program of the American Brass Band performed on February 3, 1851:5

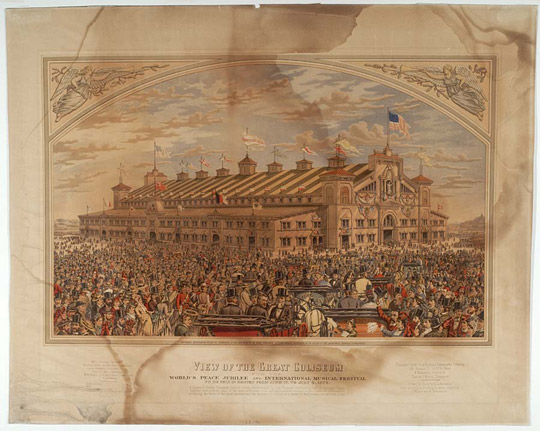

- Back to Top -BRASS BANDS AND THE CIVIL WARBy the time war was declared between the states in 1861, brass bands were abundant across America. Bands not only played concerts but also participated in political rallies, parades, picnics and dances. Many bands were also attached to local militias. They participated in musters and ceremonies and customarily wore the uniform of their units. So it was inevitable that brass bands would become an integral part of the Civil War. Bands both in the North and the South were used at rallies to encourage men to enlist. In the Federal army were hundreds of bands representing as many regiments, since in 1861 almost anyone who could raise a regiment was given the rank of colonel and command of the outfit. A band was strong inducement to enlist. At the beginning of the war bands were plentiful throughout the armies. By late 1861, however, the realities of the cost of what now appeared to be a lengthy war prompted a reduction in the number of active bands in the war effort. Dictates from the War Department terminated the establishment of new regimental bands and the replenishment of vacancies in existing bands. Benjamin F. Larned, Paymaster-General of the Army, estimated that the Federal Government could save $5 million annually by abolishing all regimental bands, so in July of 1862 the War Department gave a directive that all regimental bands be mustered out within 30 days. Those bandsmen recruited from the infantry were transferred back to their units, while bandsmen mustered in as musicians could either be discharged, or, by their own consent, be transferred to brigade bands. The directive allowed for smaller bands -- 16 musicians maximum plus a bandleader per brigade (a brigade consisted of three or more regiments). A number of bandleaders who went home reorganized their musical units and then re-enlisted to form brigade bands. Confederate Bands, while fewer in number and smaller in size, were still a popular entity. For example, North Carolina provided a good number of bands, including two from the Moravian communities flourishing around Salem. These bands, whose duties had been limited to playing for religious and community functions, became the 21st and 26th Regimental Bands of North Carolina. A group from Bethania (mostly Moravians) became the nucleus of the 33rd North Carolina Band. - Back to Top -Responsibilities of BandsmenMilitary bandsmen on both sides of the conflict soon found their responsibilities more demanding than their initial job of playing at rallies, musters, and various social events. In addition to their assignments of leading the troops in the march and playing during battle (sometimes in the thick of it), they also had non-musical responsibilities. They served as stretcher bearers, assisted surgeons in amputations and other operations, and helped bury the dead. Julias A. Leinbach was a band member of the 26th North Carolina Band who kept a war diary. On the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863, nearly three- fourths of the men of the 26th were killed in battle. Leinbach described the events, which followed: It was therefore with heavy hearts that we went about our duties caring for the wounded. We worked until 11 o'clock at night....At 3 o'clock [the next morning] I was up again and at work. The second day our regiment was not engaged [because casualties were so high], but we were busily occupied all day in our sad tasks [of caring for the wounded]. While thus engaged, in the afternoon, we were sent...to play for the men [who were not injured], thus perhaps, [to] cheer them somewhat.... We accordingly went to the regiment and found the men much more cheerful than we were ourselves. We played for some time, the 11th N.C. Band playing with us, and the men cheered us lustily. Heavy cannonading was going on at the time, though not in our immediate front. We learned afterwards, from Northern papers, that our playing had been heard across the lines and caused wonder that we should play while fighting was going on around us. Some little while after we left, a bomb struck and exploded very close to the place where we had been standing, no doubt having been intended for us. We got back to camp after dark and found many men in need of [medical] attention. Some of those whom we had tried to care for during the day had died during our absence.... We continued our administrations until late at night and early the next morning.6 - Back to Top -Interaction between Union and Confederate BandsThe bands were important to the morale of the troops -- so much so that, on occasion, they were required to play in the very thick of battle. During the battle of Dinwiddie Court House, General Sheridan (never known for his humanitarianism) rounded up all the bands under his command and placed them on the firing line with his infantry. They were then ordered to play their gayest tunes and to "never mind if a bullet goes through a trombone or even a trombonist, now and then." Not to be outdone, a Confederate band was also ordered to the front. The commander of the 1st Maine Cavalry observed: Our band came up from the rear and cheered and animated our hearts by its rich music; ere long a rebel band replied by giving us southern airs; with cheers from each side in encouragement of its own band, a cross-fire of the "Star Spangled Banner", "Yankee Doodle", and "John Brown", mingled with "Dixie" and the "Bonnie Blue Flag".7 When the battle was not raging, the bandsmen had the more pleasant task of entertaining the soldiers in evening concerts, thus providing an opportunity for the bands to perform more challenging selections which displayed their playing skills. If the armies were in close proximity to each other, Union and Confederate bands traded selections back and forth. Lieutenant Thompson of the 13th New Hampshire describes such an incident occurring just after the Battle of Cold Harbor, June 8, 1864: This evening the Band of the Thirteenth goes into the trenches at the front, and indulges in a "competition concert" with a band that is playing over across in the enemy's trenches. The enemy's Band renders Dixie, Bonnie Blue Flag, My Maryland, and other airs dear to the Southerner's heart. Our Band replies with America, Star Spangled Banner, Old John Brown, etc, After a little time, the enemy's band introduces another class of music; only to be joined almost instantly by our Band with the same tune. All at once the band over there stops and a rebel battery opens with grape. Very few of our men are exposed, so the enemy wastes his ammunition; while our band continues its playing, all the more earnestly until all their shelling is over.8 - Back to Top -Over-the-Shoulder SaxhornsCivil War valved brass instruments are classified into four major categories: bell front, upright, circular, and over the shoulder. Subcategories include those instruments using string linkage rotary valves (similar to those found on French horns of today), and the Berliner piston valve. The over the shoulder saxhorn is the style most often associated with Civil War bands. The "over-the-shoulder" design of these instruments allowed the sound to carry to the troops marching behind the band. It is speculated that this design was first introduced by the Dodworth Brass Band of New York City in the 1830s. In an article titled "Band Music: Then and Now" appearing in the American Art Journal, July 17, 1880, Harvey Dodworth said: Speaking of instruments, bugles used to be the principal, with trumpets, trombones, serpents and ophicleides. Then my father, Thomas Dodworth, and my elder brother, Allen invented a very powerful and effective instrument, to which they gave the name ebor corno, and it was identically the same subsequently brought out in France by Saxe [sic], and there christened the saxe-horn. But my father and brother got it up, and we used it in the old National Band, years before the Frenchmen knew anything about it. Our band changed from the bugle to the cornet principle, valves instead of keys in all its instruments, and those made for us to our order were on the principle of the Saxe instruments all the way through, except that the bells of ours were over our shoulders, and threw the sound back, instead of turned upward. Many of those olde instruments are in use yet, and hold their own even among the most modern.9 Balance of sound was undoubtedly a factor, as pictures indicate many Civil War bands using a variety of horns with bells of different horns pointing forward, backward, and upward. Allen Dodworth recommended bands whose performance was strictly military to use over the shoulder instruments and upright instruments for all other bands not strictly involved with the military. G. F. Patton (author of Practical Guide to the Arrangement of Band Music) suggested that the instruments playing accompaniment needed to point in the same direction so as to enhance the harmonic blend, while the direction of the cornets did not matter since the higher melodic line carries above the accompaniment anyway.10 - Back to Top -PROFESSIONAL BANDSNumerous musicians played important roles in fostering a band movement that would capture the imagination and hearts of Americans well into the 20th century. One reason for the incredible growth in music interest was due to the large number of accomplished musicians who migrated from Europe to live in America. As teachers, performers, and conductors, these musicians impacted the general populace most profoundly. The Dodworth FamilyThe Independent Band of New York was founded in 1825. Among the musicians in this ensemble were Thomas and Allen Dodworth, both recent arrivals to America from the British Isles. Thomas Dodworth, Sr. played trombone, while his son Allen was a gifted piccolo player who often soloed with the band. During the 1830s, as brass bands gradually replaced ensembles of mixed instrumentation, the Independent Band dissolved. However, instead of disbanding completely, about half the members stayed together to form the National Brass Band under Allen Dodworth's direction. In 1836 it became known simply as the Dodworth Band, quickly establishing an excellent reputation for high standards of performance. Harvey Dodworth, Allen's younger brother, took over the band in the late 1830s and maintained it until 1890 when he relinquished the leadership to his son Olean. On occasion two other brothers, Charles and Thomas, also played with the band. As was the custom of the day, the Dodworth band was often under contract with a military regiment. The Dodworth Band's longest attachment was with the 71st Regiment Band of New York, in which both Harvey and his younger brother Thomas served during the Civil War including the engagement at Bull Run (First Manassas). Following the war, Harvey led the band in the first concerts to be held in Central Park. Also, the band's instrumentation grew with the addition of a saxophone, bass clarinet, and two helicons. With the addition of more instruments, and thus a more flexible instrumentation, the Dodworths were able to offer the band's services for a variety of events--it functioned as a cornet band, a reed/brass band, or as an orchestra. For a time the Dodworth Band was without peer in New York City. Not until the 1870s, faced with the popularity of Patrick Gilmore's Band, did the influence of this great organization begin to decline. Nevertheless its legacy had cast a large shadow. No less than Gilmore himself wrote: brass instruments were never played with greater delicacy or refinement than by the Dodworth organization ...to be a member of this organization or to be graduated from it was to be looked upon as a star in the profession.11 In addition to running the band, the Dodworths were collectively and singly involved in other ventures: a music store, a publishing company, and a school for bandsmen that reportedly trained 50 bandmasters and 500 bandsmen for service in the Civil War.12 In time Allen retired from the band's leadership to start his own dance academy. The Dodworths' flexible and innovative thinking allowed them to bridge the trends of the professional band before, during, and after the Civil War when the instrumentation of bands went from woodwinds and brass, to strictly brass, then gradually back to woodwinds and brass. - Back to Top -Great EntertainersPeople have always enjoyed entertainment, often paying exorbitant amounts to attend events. As a result, contemporary society has made multimillionaires of any number of entertainers and athletes. When one attends a professional sports event or a rock concert, even though multiple thousands may be in attendance, ticket prices are exorbitant--the justification being that you won't see anything quite like "this" anywhere else. So it was in America during the 19th century. People were always looking for something bigger or more spectacular to capture their imaginations. Ole Bull, the virtuoso violinist, performed in two hundred concerts between 1843-1845 and grossed four hundred thousand dollars before returning to Norway. He literally "played to the audience" with his lavish rendition of "Yankee Doodle" and tugged at the patriotic heartstrings when he played the Grand March to the Memory of George Washington. Or consider the spectacle of pianist Henri Hertz who arrived in American at the end of Bull's sojourn and remained for six years. His spectacular trills, runs, and arpeggios dazzled the audience as much as the advertised one thousand candles used to light the performance hall. Liberace had nothing on Hertz. The visual and sound spectacle added something of a P.T. Barnum quality to the performance, and indeed Barnum himself was the agent for the soprano Jenny Lind when she toured America. For her efforts she pocketed one hundred thirty thousand dollars in profits after two years of concerts. All of the above suggests that America was ripe for a flamboyant conductor heading a world class ensemble. The first was a Frenchmen named Jullien, who conducted an orchestra in a series of extraordinarily popular concerts in America. Upon his return to Europe an Irish immigrant named Patrick S. Gilmore traveled in the United States and other parts of the world with a concert band the likes of which no one in America and perhaps even in Europe had previously heard. The year he died a young upstart named Sousa formed a professional band which would thrill audiences (albeit with more music and less hype) for decades. During the time of Gilmore's and Sousa's success there were thousands of concerts played by innumerable professional and community bands across the country. From the end of the Civil War until the Great Depression these bands were the heart and soul of music-making in the U.S. - Back to Top -Monsieur Antoine JullienJullien's ShowmanshipDespite his acknowledged high level of musicianship, Antione Jullien was not above plenty of hype when he was performing before an audience. For example, whenever Beethoven was about to be played Jullien would precede the performance with a ritual in which he turned back the cuffs of his coat and the white lacy wristbands of his shirtsleeves. At this signal someone would bring out a silver tray upon which lay a jeweled baton and white kid gloves. With great care the gloves were put on and the baton picked up, with the assistant departing after a low bow. After a pause as if to pay homage, the music would finally begin.2Antoine Jullien was trained at the Paris Conservatory before embarking on a career as a composer and conductor, first in Paris at the Jardin Turc. In 1838 he went to London where he was successful as a conductor of promenade concerts, balls, and festivals. Fifteen years later the lure of success and money in America set up six months of concertizing. He took a group of 27 instrumentalists whom he augmented with over 60 local musicians in New York and began promoting a series of "Monster Concerts for the Masses" which began at Castle Garden on August 29, 1853. After a six-month tour of the country he returned to New York in May 1854 where he gave a series of farewell concerts which culminated at the Crystal Palace with a "Grand Musical Congress" managed by P.T. Barnum, involving 1500 performers. The repertoire consisted of serious works of European composers as well as efforts of Americans, such as the symphonies of William Henry Fry. Lighter repertoire consisted of polkas, quadrilles, waltzes, and novelty pieces. Among the players, Theodore Thomas was chosen as a first violin. In time Jullien triumphantly returned to Europe, but eventually met with financial disaster, and died in an insane asylum near Paris in 1860. - Back to Top -PATRICK S. GILMOREBorn in County Galway, Ireland on Christmas day in 1829, Patrick Gilmore joined a military band stationed in Canada at age 18. After one year he left military service and moved to Boston, establishing a reputation as a cornetist. When he was 23 he accepted the leadership of the Boston Brass Band--the first leader of the ensemble to play cornet, as the other three, Ned Kendall, Joseph Green, and Eben Flagg, were all virtuosos on the keyed bugle. After three years Gilmore was approached with an offer to lead the Salem Brass Band with the promise of "one thousand a year and all the money he can make." He accepted. The Salem band's fame led to many engagements, including leading the Guards Militia Company of Charleston down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington during the inaugural parade for James Buchanan--much to the frustration of the other Boston bands who felt the honor should have gone to them. It was just prior to this event that the great playoff between Gilmore and Kendall occurred. Gilmore vs. KendallNed Kendall was revered in New England as the greatest keyed bugle player of his time. His prowess was such that music deemed technically too difficult for the instrument, was mastered by this celebrated musician. Kendall, upon visiting England, was pleased to find that his reputation had preceded him across the Atlantic. In December 1856 Gilmore announced a concert in which Kendall would be guest soloist with the Salem Brass Band, with Gilmore conducting. Kendall was scheduled to play a variety of solos, followed by a contest between Kendall on the keyed bugle and Gilmore on the cornet. For the contest Kendall was to play each section followed immediately by Gilmore's repeat of the famous bugle feature Woodup Quickstep. The first half of the concert was a triumph for Kendall who endeared himself to an audience who had assembled to hear one of America's most celebrated musicians. However when the contest began, the deck was clearly stacked in Gilmore's favor. The cornet was a far superior instrument to the now outdated bugle, which could not keep up with the rapid facility that the cornet provided for Gilmore. Gilmore simply played faster and cleaner on a piece which, while very difficult on keyed bugle, provided no insurmountable problems when played on the cornet. Gilmore, ever the gentleman, at the end of the contest quietly asked Kendall to take the podium and conduct while Gilmore sat in the ensemble as a section player--perhaps his only time to play under the legendary musician. This meeting could only hasten the demise of the bugle and provide more opportunity for valved instruments, such as the saxhorn, to become the instrument of preference.13 It also didn't hurt Gilmore's growing popularity as a soloist and bandleader. - Back to Top -Civil War EngagementAfter five successful years at Salem, Gilmore was lured back to Boston where he took over the Boston Brigade Band. He changed the name to the Gilmore Band and took complete control of the operations of the ensemble, including expenses such as uniforms, rehearsal hall, and music, as well as collecting all the profits.14 This ensemble was similar to the Dodworth Band in that it had a large flexible instrumentation capable of providing music for a variety of venues.15 During the Civil War Gilmore and his band enlisted as a unit in October, 1861 and served with the 24th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment until the dissolution and mustering of all volunteer bands in August 1862. At first no one dreamed the war would last as long as it did, so after 10 months of service, with no immediate end in sight, most volunteer bands went by the wayside in a cost-cutting procedure. Back in Boston, Gilmore conducted a number of concerts to keep the morale up during the time of war. Music selections were diverse, with light selections including Oh! Susanna and Nelly was a Lady intermixed with hymns such as Nearer My God to Thee and patriotic numbers including Battle Hymn of the Republic. Meanwhile the Governor of Massachusetts asked him to reorganize the military bands in the state. Gilmore sent out a number of new bands and even accompanied one to New Orleans, where General Banks requested that he be in charge of all music under his command. It was during this time that Gilmore had the opportunity to create the first of many band extravaganzas that would make him a celebrity.16 The First of Several Oversized ConcertsOn March 4, 1864, at the request of General Banks, Gilmore oversaw the music celebrating the inauguration of Governor Michael Hahn. For the event Gilmore created a Grand National Band consisting of 500 Army bandsmen plus addition drum and bugle players. He also organized a chorus of 5000 children. In addition to many other patriotic tunes, during the last number, Hail Columbia, Gilmore shot off thirty-six cannon by electric buttons from the podium. As the cannon fired methodically in time with the beat, the bells from churches and cathedrals throughout the city chimed to create a most spectacular effect. It was a sensational event, on the order of something Jullien would have conceived, and undoubtedly whetted Gilmore's appetite for similar events in the future.17 Afterwards, Gilmore, sensing the end of the conflict, wrote the music and words to When Johnny Comes Marching Home under the pen name Louis Lambert, which became a popular song selling copies by the tens of thousands.18 - Back to Top -National Peace JubileeThe "Anvil Chorus"The high point of the opening concert of the National Peace Jubilee undoubtedly was the "Anvil Chorus" from Il Trovatore during which Gilmore, six-foot baton in hand, directed the thousands of musicians present with the aid of fifty firemen pounding anvils, as well as multiple cannon fired in synchronization, augmented by church and cathedral bells.3After the war Gilmore returned to Boston and provided audiences with music as he had done in the past. At the same time he dabbled in and out of the instrument manufacturing business. However, Gilmore grew restless, so in 1867 he embarked on his next great venture. As Gilmore later wrote: A vast structure rose before me, filled with the loyal of the land, through whose arches a chorus of ten thousand voices and the harmony of a thousand instruments rolled their sea of sound, accompanied by the chiming of bells and the booming of cannon, all pouring forth their praises and gratification in loud hosannas with all the majesty and grandeur of which music seemed capable. The ensuing National Peace Jubilee of 1869 was an enormous undertaking. Gilmore had to rely on all the methods of persuasion at his disposal to pull off such a monumental project. The logistical nightmare included building a hall that would seat up to 50,000 and finding over 1000 instrumentalists and 10,000 singers from various cities. He then had to arrange for all the musicians to arrive at Boston at the same time, coordinate their arrival at the hall, arrange for the rehearsal, and work with the school system to create a large children's chorus. Gilmore also secured the services of E. & G. G. Hook to build an enormous pipe organ for the occasion. Eventually he secured the support of enough musicians, educators, and businessmen to bring the colossal event to fruition. It was a resounding success. Performances were given over a five-day period in which Gilmore put the massive forces at his disposal to good use. Ole Bull served as concertmaster, while Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the words for a Hymn of Peace. President Grant and the entire cabinet were in attendance.19 The celebration continued for five days. After the opening concert came a symphony and oratorio concert followed by a "People's Day". The fourth concert was more classically oriented (Beethoven's Fifth Symphony) while the final concert featured the huge children's chorus. Following is the program for the "People's Day":

- Back to Top -The World Peace JubileeWith part of the profit that Gilmore realized, he and his wife Ellen took an extended trip to Europe. Perhaps it was here that he got the idea for his next big adventure--a monster concert with double the forces of the National Jubilee. So in 1872, the World Peace Jubilee was held. Gilmore developed a band and orchestra of two thousand performers and a chorus of twenty thousand to perform in a coliseum with a capacity of one hundred thousand. In addition to these forces he added a number of ensembles from Europe: the Band of the Grenadier Guards under Daniel Godfrey, the Emperor William's Household Cornet Quartette, the orchestra of Johann Strauss, with Strauss conducting, the Kaiser Franz Grenadier Regiment Band under Heinrich Saro, the National Band of Dublin under Edwin Clements, and the Garde Républicaine Band under Paulus. Among the American bands present were the United States Marine Band under Herman Fries and the New York 9th Regiment Band under D. L. Downing. Outside the event itself, Americans benefited from the opportunity to hear some of the best ensembles of Europe. The superiority of the Europeans' musicianship provided the Americans a standard for which to strive during the next decades.20 For the most part, the siren song for creating gargantuan concerts had now left Gilmore. This allowed him to devote his time and energy to developing a first class touring ensemble--an effort which was perhaps his greatest legacy. - Back to Top -Gilmore's ContemporariesAfter the Civil War, with the exception of Gilmore's Boston band, New York City was home to the best bands in America. The premiere band undoubtedly was the Dodworth Band. Allen Dodworth and his younger brother Harvey not only maintained high standards of musicianship, but, as already mentioned, were also innovators in instrumentation, Harvey having introduced the saxophone, bass clarinet, and tuba to American bands. Harvey had assumed leadership of the 13th Regiment Band in 1839 at the age of seventeen. In 1860 Allen retired from band directing to pursue teaching and coach dancing. Harvey, at his brother's urging, accepted leadership of the Dodworth band, but popular demand forced him to continue with the 13th Regiment. So, Harvey found himself in the position of simultaneously directing two of the best bands in New York. Although, the 13th Regiment Band was considered the fourth best band in the city, in 1867 it became the "official" Central Park Band and enjoyed the patronage of thousands of New Yorkers who attended the summer concerts.21 The 7th Regiment Band under the leadership of C. S. Grafulla was the chief rival of the Dodworth band. Grafulla, a prolific arranger for band music, compiled one of the best band libraries and directed his ensemble in outstanding performances. The competition was fierce between regiments of the New York National Guard, and the notoriety showered on the bands of the 13th and 7th was apparently too much for Colonel James Fisk, Jr. of the 9th Regiment. In 1870 he called in D. L. Downing, who had a reputation as a bandmaster, composer, and arranger, to build a band second to none. In three years Downing built an extensive library and hired some of the best musicians available, creating what was considered the third best group in the city by establishing a standard of performance that was widely praised. - Back to Top -Gilmore's BandNot to be outdone by the other bands in the city, the 22nd Regiment pursued the only other bandleader in the United States whose band was comparable in quality to these New York ensembles. In 1873 Gilmore accepted the leadership of the 22nd Regiment Band of New York, stipulating the same conditions he negotiated with the Boston Brigade Band fourteen years earlier. This ensemble, universally known as Gilmore's Band, became an oustanding ensemble, enjoying an international reputation. Soloists included Matthew Arbuckle and Jules Levy on cornet and Frederick Innes on trombone. Building a band in New York when there were several fine ensembles already established made it no easy task to find steady engagements. The problem was exacerbated by the financial panic of 1873--a time when many banks across the nation failed. Gilmore realized it was in his best interests to travel to other cities where outstanding bands were not so entrenched. The band toured the United States and Canada several times, including Europe in 1878, extending Gilmore's reputation farther than ever before. Orchestras in America were, at best, still struggling, so it was through the efforts of the professional bands such as Gilmore's that the general populace was first introduced to the music of the great masters. By now professional bands had long since evolved past the brass band of Civil War times and the instrumentation of Gilmore's band reflected instrumentation similar to contemporary practice. Following is the instrumentation used for the European tour:

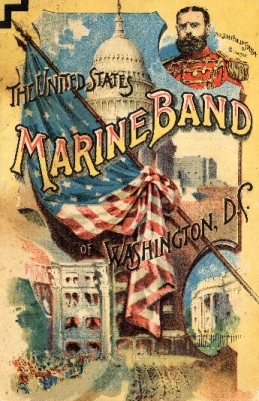

This instrumentation allowed for a wealth of color possibilities not previously enjoyed by American ensembles. Eventually, Gilmore's band was considered without peer in America, if not the world, and engagements were plentiful. By 1880 a typical year's engagements consisted of a summer concert series at Manhattan Beach, winter concerts at Madison Square Garden (formerly Gilmore Garden), and tours during the fall and spring under the management of David Blakely. Through his nationwide tours--and he was essentially the only touring band of the time--the general populace not only enjoyed the popular music of the day but were exposed to the music of the European masters. Where else would they hear the music of Wagner, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Rossini, Verdi, etc.? Gilmore's library had amassed ten thousand pieces, and he employed two or three men to write new arrangements for the band. It was said that the players were so accomplished that they could read many of the most difficult arrangements at sight without the need for rehearsal.23 The end came unexpectedly during a tour in the fall of 1892. Gilmore had planned what he referred to as the Columbian Tour in which he enlisted the participation of one hundred players. He was to open the tour at the St. Louis Annual Exposition and arrive back in New York at Christmas. The band made the trip to St. Louis and had begun their engagement of concerts. Gilmore conducted his last concert on September 23, and died in great pain the next evening in his room at the Linden Hotel. Charles W. Freudenvoll, the assistant conductor, had visited Gilmore that afternoon and was conducting the concert in Gilmore's absence when word arrived of his death in the middle of the program. The concert ended with word of Gilmore's death announced by Frank Gaiennie, general manager of the exposition. The next morning the band marched at the head of a cortege to the train station where Gilmore's body would be transported back to New York for burial. They played Gilmore's own composition Death at the Door and Handel's "Death March" from Saul.24 Efforts were made to keep the band together. D. W. Reeves tried unsuccessfully to tour with the group, as did Victor Herbert who did a credible job for a few years. Herbert's other musical interests were too time-consuming, and he resigned in 1897. It could be said that no one else had the ability to sustain an organization of this caliber other than Gilmore. Yet it must also be acknowledged that Reeves and Herbert were operating at something of a disadvantage. Within a year a number of players had "deserted" the Gilmore band to perform under the baton of a much younger director who had just started his own professional band--John Philip Sousa. - Back to Top -CONCERT SOLOISTSToday a highlight of many band concerts, especially summer park concerts or the marvelous concerts performed by professional service bands, is the featured soloist playing with the entire ensemble as accompaniment. While audiences marvel at the technique displayed by these principal chair players, and while a fair number of these musicians have established name recognition, interest today in this type of playing pales in comparison with that of the golden era of the professional band. Players on various instruments were featured from time to time, as well as vocalists singing the popular songs and arias of the day. However, no group of soloists seemed to capture the imagination of the populace as the cornet soloists. The cornet was the logical replacement for the keyed bugle that had been the solo instrument of choice some years earlier. No doubt Patrick Gilmore himself, having been a soloist of notoriety before taking the podium permanently, had a preference for this agile instrument. The list of cornetists who became household names was formidable. Gilmore at one time or other had under his baton Matthew Arbuckle, Jules Levy, Alessandro Liberati, Ben Bent, and Herbert L. Clarke. In addition to the personal confidence, discipline, and outstanding musicianship that drove these men to perform in front of the public night after night, most of them enjoyed an equal dose of ego to sustain them. Some egos were more famous than others. Charles Seymour, who became a respected soloist and bandmaster in the St. Louis area, relates a personal observation upon attending a Gilmore concert in his younger years. Seymour went to the concert to hear Ben Bent, whom he admired. Much to his surprise, Bent did not play one note during the concert. Upon inquiry he discovered that Bent was engaged to play only when Arbuckle lay out to rest. As the story goes, Arbuckle was so incensed at having the younger player as an understudy for his position that Bent played nary a note the entire season. Arbuckle's frustration was just beginning because the next year Gilmore employed Jules Levy as cornet soloist. His Own Greatest FanJules Levy's prodigious ego was easily observed in his attire. He refused to wear the uniform of the 22nd Regiment, preferring to wear a dress suit adorned with his medals and a monocle stuck in his eye. The battle of the soloists went well for Gilmore and the press for some time until one night the battle turned into a brawl. Gilmore intervened, but not before tearing Levy's coat and messing up Levy's medals.A furious Levy immediately challenged Gilmore to a duel to the death with pistols. Cooler heads prevailed upon Levy to agree to pistols at a shooting gallery, with the winner picking up the tab for dinner for the whole crowd at Delmonico's. Six shots were allowed apiece, with Gilmore eventually winning what some observers acknowledge was a contest fixed in Gilmore's favor. Upon reading of the setup in the next morning's paper, Levy was filled with anger and shame. He left Gilmore's organization and led a checkered career to the end of his life. Another example of his egotism occurred when he was making an appearance in 1890 with the City Guard Band of San Diego. Arriving after the band had started playing, Levy heard the applause that was being acknowledged by R. E. Trognitz, who had just completed a solo on the alto saxophone. Levy cried, "That's for me." He then shoved Trognitz aside and took the bows himself.4 It was paramount in publicity to use whatever inflated or colorful description one could get away with when describing a performer, as this would whet the appetites of the public to come to the concert. So it is no surprise that the "Phineas T. Barnum" in Gilmore led him to use descriptions such as "the greatest living cornet player" and "the great favorite American cornet player" when billing Levy and Arbuckle, making each feel that perhaps they had received top billing.25 There was at least one incident in which Gilmore's sense of promotion probably got the better of him. The rivalry between Arbuckle and Levy was anything but a secret, so Gilmore, realizing that each had their own following of admirers, decided to make the most of this battle of egos and boost ticket sales in the process. Gilmore let little hints drop with the press, who in turn devoted columns to the bitter rivalry between the two superstars. Then the public got involved, siding with their favorite player: When Arbuckle played his solo, his fans applauded and whistled, while the Levy crowd sat on their hands and booed. When Levy played, his cohorts made the garden resound with their bravos, while the Arbuckle clique hissed.26 To the audience's credit there was a difference between the two players. Levy was a great technician who loved to take a simple song and embellish it with intricate variations, while Arbuckle, who also was blessed with technique, preferred to inspire the audience with his beautiful tone and musical turn of phrase. Hi Henry, a cornetist himself and leader of Hi Henry's Minstrels, was in attendance for some of these programs and wrote: A just comparison of these two great artists is no disparagement to either. They were not at all comparable. Levy may be said to play that which no other living man can as brilliantly repeat. Arbuckle, while playing nothing others could not render, delivered it in such finished style that none could simulate it. Other soloists enjoyed fame with various bands, including Frederick Innes and Arthur Pryor on trombone, Simone Mantia on euphonium, and Bohumyr Kryl and Herman Bellstedt on cornet. A number of these eventually formed their own bands, notably Innes, Pryor, and Kryl. - Back to Top -JOHN PHILIP SOUSARenowned to this day as the March King, perhaps no bandmaster has enjoyed as much notoriety as John Philip Sousa has. Sousa was born on November 6, 1854 in Washington D. C. where his father had taken a position as a trombonist in the U.S. Marine Corps Band. He learned to play the trombone, baritone, E-flat alto horns, and cornet, but his principal instrument was the violin. In June of 1868 Sousa enlisted as an apprentice for the Marine Band where he served for almost seven years. For the next five years he played in or conducted a variety of theater orchestras, including the orchestra directed by Offenbach at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. During this sojourn in Philadelphia, Sousa heard Gilmore's band for the first time. In 1879 he conducted Arthur Sullivan's H.M.S. Pinafore with a touring company, and in 1880 he composed and compiled music for a variety show, Our Flirtations, then took it on tour. While on tour in St. Louis he received a telegram inviting him to become the fourteenth director of the Marine Band, a position he eventually accepted. The Marine BandThe Marine Band Sousa inherited had little semblance to the Marine Band of today. The literature selection was archaic and a high level of performance standards was lacking. Sousa straightway ordered music from European composers so the band's literature would reflect the contemporary composers of the day. He then proceeded with more rigid rehearsals than the men were accustomed to and set in motion procedures that would allow disgruntled bandsmen to seek a quick discharge. The membership shrank to thirty-three, providing Sousa the opportunity to recruit younger replacements, which soon brought the band back to original strength. Sousa reorganized and reshaped the Marine Band into a first-rate performance ensemble. These improvements elevated concert attendance in the thousands. The Marine Band was also considered an outstanding marching unit--something for which his professional band would never be noted.27 The March KingSousa was a rather prolific composer who especially enjoyed writing art songs and operettas that were somewhat in the style of Jacques Offenbach and Sir Arthur Sullivan. His compositions in these genres have been relegated to obscurity, but Sousa will always be known for his marches, the art form in which he was most successful. From his first march, The Review (1873), to The Northern Pines and Kansas Wildcats (1931), Sousa wrote at least 136 marches, giving him the title of the "March King". The Gladiator and The Rifle Regiment (both 1886) brought Sousa his first popular success, while the addition of other notables such as Semper Fidelis (1888), The Washington Post (1889), and The High School Cadets (1890) increasingly made Sousa a household name. Dealers ordered piano arrangements of these marches in lots of 20,000. The Washington Post enjoyed international success because of a new dance craze, the two-step. In Europe the two-step was often referred to as a "Washington Post". His popularity continued with such favorites as The Liberty Bell and Manhattan Beach (1893), King Cotton (1895), Hands across the Sea (1899), The Stars and Stripes Forever! (1896), The Fairest of the Fair (1908), and The Gallant Seventh (1922), to name a few. - Back to Top -Sousa Forms His Own BandIn 1892 Sousa made two decisions which would make him a wealthy man. First, he negotiated royalty contracts for the publication of his music in lieu of flat fee payments, and second, he resigned from the Marine Band and formed his own professional band.28 While on tour with the Marine Band in 1892, Sousa was approached by David Blakely who had managed several tours in the past for Gilmore. Blakely, speaking on behalf of a syndicate of businessmen, offered him four times his military salary of $1500, plus twenty percent of the profits, to form and direct a professional band. Sousa accepted. Sousa's band soon established itself as the foremost professional band in America if not the world. As fate would allow, Sousa formed his band right at the time of Gilmore's sudden death. Its first concert was presented at Plainfield, New Jersey, on September 26, 1892, two days after Gilmore's death. The instrumentation of Sousa's Professional Band in 1892 parallels today's standards:

After a somewhat rocky first year, Sousa prepared for another season in 1893 by rehearsing the band for an extended engagement at the Chicago Exposition. He had added nineteen players from Gilmore's band, including soloist Herbert L. Clarke, and was undoubtedly anticipating having a better quality group than he had the previous year. This was an opportunity for Sousa to establish his name and ensure the success of the band for years to come. H. W. Schwartz described the first rehearsal in New York during April: For two and one-half hours in this first rehearsal he drilled the different sections of the band on how to play sixteen bars of an overture! He started with the clarinet section. If this section had been a bunch of dubs, the long time he spent with them would not have been so remarkable, but these men were the cream of clarinet players, the best in the land, each chair occupied by a finished artist, personally selected by Sousa for the job. First Sousa asked the solo clarinet to play a few bars of the music alone. This he did, and to other members of the band his playing was above criticism. Then Sousa asked him to play it again, this time using a little different breath control and somewhat different phrasing and tone quality. The solo clarinet began to sweat, and he became a bit irritated when Sousa asked him to play it again and again, like a beginner. Finally he grasped what Sousa was striving for, and when he had played it to Sousa's satisfaction, he was a little surprised at how much more musical it sounded. Then Sousa turned to the assistant solo clarinet and asked him to play it exactly the same way. After a few trials the assistant solo clarinet protested that it was asking too much to expect his playing to sound the same as that of his partner. He had his own style of playing, he said, and he had his own individual quality of tone. Patiently Sousa persisted and asked him to try it. Eventually the second man played the passage so it was indistinguishable from that of the first. Then Sousa proceeded to the next stand of first clarinets, and in time this man was playing the passage so it had the same sound produced by the first two men. Eventually Sousa had all six first clarinetists playing the passage with the same breath control, same phrasing, and same quality of tone, and when they played together, they played as one man. The same procedure was followed with each section in each family of instruments. Each part in those sixteen bars was played again and again, until every man in the band was breathing and phrasing and interpreting the music so that the whole ensemble blended perfectly and performed smoothly as a unit. At no time did Sousa show impatience, but neither did he compromise with a single man or a single note. The skepticism and even rebellion of the men were turned to admiration and wholehearted co-operation . . . Sousa dismissed the band with this parting shot: "Now, gentlemen, you know what I want in the future. You reed players will discard your coarse military reeds and adopt the narrow, light symphonic reeds. And you cup mouthpiece players will look to your mouthpieces and play with a delicate embouchure. Forget how you may have played in other bands. I want this band to play great music with the precision and polish of the finest symphony orchestra."30 Sousa worked very hard to please the audience wherever he went. His success is noted in the fact that even when all other touring professional bands were defunct, the Sousa band continued to play to enthusiastic audiences. A typical program consisted of nine selections, which by appearance would seem like a fairly short concert. Sousa, however, was not one for milking applause from the audience, so between numbers he inserted up to two encores, always before the applause had an opportunity to die down. The encores might be light classics or a popular tune, or, as one might expect, a march from his own pen. Sousa felt the encores kept the audience from becoming restless from too much time in between selections, and also added an element of surprise and anticipation from both audience and performer alike. Sousa would announce an encore to the players within earshot during the applause, and word would then spread rapidly through the ranks. With little or no time to find the written music, it was up to the veterans of the band to play from memory until the less experienced bandsmen could locate the selection and eventually join in. Soloists were always an important part of the concert repertoire, and Sousa usually featured one of his best players second on the program after the opening selection and two encores. Soloists included Arthur Pryor on trombone, Herbert L. Clarke, Frank Simon and Bohumir Kryl on cornet, and J. J. Perfetto and Simone Mantia on euphonium. To add a touch of elegance to the concerts Sousa also included female soloists in his concerts, including singers, violinists, and harpists. The coloratura soprano Estelle Liebling estimated that she sang over 1600 concerts with the band.31 Representative programs of the Sousa Band at the turn of the century follow:

Notice that Sousa not only incorporated music of well-known Europeans, but also kept up with contemporary tastes as well with his selections of new music. During his second European tour (1901) Sousa gave a surprise birthday concert at the request of King Edward VII of England. Six of the eleven numbers requested were Sousa's own compositions, while Arthur Pryor and Herbert L. Clarke had one each:

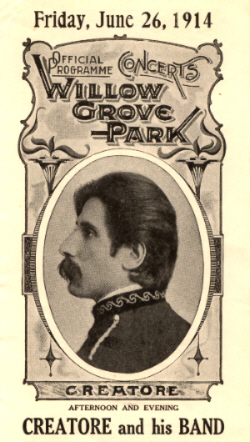

Seven encores were also selected, mostly by the king.33 Sousa and his Band toured the United States yearly, made four tours of Europe between 1900-05, and took one world tour (1910-11). During WWI the band was inactive while Sousa served in the U.S. Navy. He organized band units and toured with the Jackie Band--an ensemble of more than 300 sailors formed to aid the war effort. After the war the Sousa Band actively toured again until the Depression and Sousa's declining health brought the band's demise in 1931. - Back to Top -CREATORE AND THE ITALIAN INVASIONAt the turn of the century, word came to Italy that opportunities were abundant for musicians in America. The result was over a dozen Italian bands storming America's shores seeking their fortune. At first they enjoyed the promised success, but over time the sheer numbers of bands advertising the Italian mystique proved to be too much. All this came from the popularity of one man--Giuseppe Creatore. Creatore was a trombone player in Ellery's Royal Italian Band, which arrived in New York City from Naples in 1899. This fifty-five-member ensemble became known simply as the Italian Band. The Italian Band was not an especially polished ensemble, but being from Europe surely didn't hurt their prospects for employment either. It was during an engagement at Willow Grove in Philadelphia that Creatore went from trombonist to conductor in one of those storybook situations in which the conductor becomes ill and a member of the ensemble takes the podium at the last second. Creatore conducted with such authority, flamboyance, and energy that he was an immediate success. Successive performances allowed him to solidify his superiority over the regular conductor to the extent that at the end of the tour a number of the musicians cast their lot with Creatore, who formed a new band. It was in the fall of 1901 when Creatore returned to Naples to recruit musicians that he boasted about the concerts, touring, favorable reviews, and contracts that he enjoyed in America. Indeed he was a sensation. He returned to New York in 1902 with his band of sixty hand-picked men. His engagement at Hammerstein's Roof Garden eventually played to standing room only, and the headlines exclaimed: "A SVENGALI TO HIS BAND" and "WOMEN ON TABLES IN HYPNOTIC FRENZY". He was reported to have created a hypnotic spell over the musicians--one that exacted the most inspired performance. Stories claimed he also had a spell over the audience, especially the women who reportedly jumped on the top of tables and writhed and emoted as if in a frenzy. For a time, Creatore was paid top dollar and was booked months in advance, enjoying widespread acclaim. It was as if America finally had another Jullien to embrace. While Creatore was on tour in Kansas City, the music critic for the Journal explained the phenomena thus: Creatore starts the band in a mild, entreating way. A simple uplifting of the arms. Then suddenly, with a wild shake of his shaggy head, he springs across the stage with the ferocity of a wounded lion. Crash! Bang! And a grand volume of sound chokes the hall from pit to dome. Then he doubles up like a question mark and, with glaring eyes and gritting teeth, with oustretched prompting finger, creeps stealthily around, the very picture of hate and malice personified. Suddenly a wild leap into the air, and with his long hair standing straight up, he lands like a bucking bronco. Now he leans over the row of music stands, he smiles the smile of a lover--pleading, supplicating, entreating, caressing--with out-stretched hand, piercing the air with his baton, like a fencing master. Almost on his knees, he begs, he demands, he whirls around with waving arms. He laughs, he cries, he sings, he hisses through his clenched teeth. He feels the music with every fibre. Now it is the rushing winds; now the mad plunging of galloping hours; now the booming of the surf on bleak rocks; and now the birds singing in the treetops, the sound of angel's wings. He throws up his hands like an Aztec in prayer, there is a wild burst of melody and it is over. He bows and smiles, then goes behind the scenes and combs his hair.34 Creatore had his share of critics who felt his conducting was excessive, flagrant, and overly sentimental. The excess of Italian bands fighting for engagements, coupled with the waning market for emotional Italian conductors, eventually brought an end to Creatore's meteoric rise to stardom. - Back to Top -PATRICK CONWAYPatrick Conway spent most of his life in central New York State. Born on July 4, 1865, he began playing cornet on his doctor's suggestion that it might strengthen his lungs (his father, two sisters and a brother all died from tuberculosis). In time he studied music at Cornell and the Ithaca Conservatory. In 1895 Conway was engaged to teach music at Cornell University where he organized the Cornell Cadet Band and directed it for thirteen years. It was during this time that the City of Ithaca requested him to organize a city band. This ensemble grew in prestige and at the turn of the century took its first tour. This led to engagements at Willow Park in 1903, and beginning in 1906 at Young's Pier in Atlantic City, which would last for many years to come. During this time Conway became friends with Sousa, as their bands frequently played engagements at the same locations.35 For example, in 1915 Conway's and Sousa's bands were engaged at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, as well as Charles H. Cassassa, whose band was the official band of the exposition. On several occasions the bands combined forces, with each conductor sharing the podium in front of some 170 musicians.36 In 1908 Conway moved to Syracuse, N.Y. to organize and conduct the Syracuse Symphony as well as to direct the leading theater orchestra of the city. However, each summer he continued to tour with "Patrick Conway and his Band"--an ensemble of fifty to sixty select musicians, as well as a dozen soloists. He also became a recording artist for the Victor Talking Machine Company of Camden, N.J., where he turned out dozens of recordings.37 In 1916 Conway accepted a captain's commission to organize an official band and head up a music program for the Air Service--an effort which is considered the predecessor of the U.S. Air Force Band. His experiences teaching in Ithaca, coupled with his experience in the military, prompted Conway to establish the Conway Military Band School in 1922 as an affiliate of the Ithaca Conservatory of Music. Conway's motivation to establish the school was at least twofold. First, he realized that the era of professional bands was in decline and they would not maintain the level of popularity enjoyed over previous decades. Second, he correctly observed that school band programs would become a dominant influence in maintaining the band heritage. During this time most band directors in the education field lacked formal training, while conversely, performers in professional bands had limited teaching experience. Conway's Military Band School allowed the professionals to pass on their expertise to students in a structured educational environment. The school attracted serious students from all over the country who learned to be competent performers and conductors.38 Conway was a cornet soloist but did not solo with his band. He never toured extensively, nor did he use gimmicks to advertise his band. He could not provide his musicians permanent employment but was able to employ the finest musicians for brief engagements. Unlike many other conductors his baton technique was most conservative. What made an impression on the listening public were high quality performances of musical excellence. What made an impression on the musicians under his baton was not only his musicianship and skill in molding together a first-class ensemble but also his demeanor as a gentleman. - Back to Top -FREDERICK INNESFrederick Innes deserted the band of the First Life Guards in England to come to America. He served in Gilmore's band and the Boston Brigade Band where he developed a reputation as a trombone soloist--a reputation which allowed him to return to Europe and appear in that capacity in Hamburg, Berlin, Vienna, and Paris, as well as his home in England. He returned to the U.S.A. in 1880 at Gilmore's behest to compete with Jules Levy. His habit of playing cornet solos on the trombone both infuriated Levy and impressed the audiences. In 1887 Innes formed his own band and began touring the country. For some years he directed the 13th Regiment Band of Brooklyn, N.Y. before accepting the same position with the Denver Municipal Band in 1914. Two years later he resigned that position to form the Innes School of Music. In 1923 he became president of the Conn National School of Music in Chicago. As a performer, Innes was considered by Sousa and Clarke to be the best of his time. As a conductor he was noted for adding chimes, double bass, and harp to the band instrumentation. Innes' repertoire tastes included conducting entire concerts of the music of Wagner and playing transcriptions of entire symphonies. He conducted all his concerts by memory.39 - Back to Top -ARTHUR PRYORHaving played about 10,000 solos in his career, Arthur Pryor was known as the "Paganini of the trombone". His playing expressed a lyricism coupled with dazzling technique that was perhaps unequaled for his time. Pryor came to the Sousa Band as trombone soloist in 1892, leaving a position as conductor of the Stanley Opera Company. He became the star attraction of Sousa's band, also serving as assistant conductor from 1895 to 1902.40 "Paganini of the Trombone"At a performance in Leipzig before an audience estimated at twenty-five thousand, Pryor received a tremendous ovation. At the intermission members of the Gewandhous Symphony Orchestra came to the stage to disassemble his trombone and inspect it, questioning how anyone could achieve technique on the trombone such as Pryor's without the benefit of some mechanical aid. The only aberration from the norm was that Pryor's horn had a small bore (.458 of an inch) and a small bell (six and one-quarter inch diameter).5In 1903, the last year he played with Sousa before resigning to form his own band, Pryor was a part of the Sousa Band's European tour. His solo performances were most favorably received. In England the Birmingham Post said: A trombone solo Love Thoughts contributed by Mr. Arthur Pryor was an achievement quite unique. The player realized a tone quality which no other soloist on that instrument has ever produced, and yet in the way of rapid scale passages, his performance was especially astonishing. The Dublin Mail wrote: His execution . . . savors of the marvelous. It was almost too much to believe that such a pure and exquisitely beautiful tone could be produced on an instrument, whose usual characteristics are aggressive. As director of his own band, he made six nationwide tours between 1903 and 1909 before settling in to less stringent engagements at Asbury Park, New Jersey, Willow Park Grove, New Jersey, and Royal Palm Park, Miami, Florida. He retired in 1933. Pryor made some 1000 recordings with his band before 1930. He also directed the Sousa Band in several recordings, even after he had left the group.41 - Back to Top -

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||