12

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

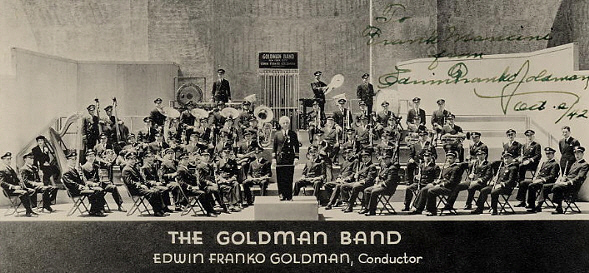

The need for a new library of original band music of artistic and imaginative merit became and still is the objective of all musicians who believe in the unlimited scoring potentials of the wind-percussion ensemble. The time has come to discard the old idea that a concert band is an orchestra without strings relegated to the performance of utilitarian, inferior music. The 20th century has seen a steady growth in original literature for the wind band, especially since 1940. Significant efforts have been made to improve the band's repertoire, both in substance and originality, while creating more functional and consistent instrumentation. However, this trend was been somewhat slow in coming. For decades the wind band relied on the orchestra for much of its repertoire because of the obvious similarities between the two. Using orchestral transcriptions created a "symphonic" sound for the band, and also created the tendency for composers writing original works for band to incorporate something of an orchestral style in their compositional technique.2 As the previous chapters note, the wind band is not just a 20th century phenomenon. From the music of the town waits to the consorts of the Renaissance and the music of Gabrieli, to the tower music of Germany and the oboe band of Louis the XIV of the Baroque, to the Harmoniemusik of the Classical period to the French Revolution and the dawn of Romanticism, the wind band has been transformed to fit a variety of situations. But it is in the 20th century that the modern wind band finally takes its place as an art form not created to serve a strictly utilitarian function. The wind band was well respected as a concert vehicle during the age of the professional bands. The legacy of Gilmore, Sousa, and so many others was handed down to a few good ensembles - notably the Goldman Band and the military bands which have played an important role in preserving the heritage of the wind band. Many outstanding ensembles also began to form in the colleges and universities across the United States, due in no small part to the immense growth of primary school bands. But except for marches, the literature performed still almost exclusively consisted of transcriptions, primarily of orchestral works.  U.S. Marine Band, William Santelmann conducting, performing on the White House lawn on Easter Sunday, 1940 2 REPERTOIRE OF THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURYThe wind band was well respected as a concert vehicle during the age of the professional bands. The legacy of Gilmore, Sousa, and so many others was handed down to a few good ensembles--notably the Goldman Band and the military bands which played such an important role in preserving the heritage of the wind band. Many outstanding ensembles also began to form in the colleges and universities across the United States, due in no small part to the immense growth of primary school bands. But except for marches, the literature performed still almost exclusively consisted of transcriptions, primarily of orchestral works. The years 1917-1928 saw a total of forty-nine compositions for winds by composers such as Webern, Berg, Ives, Villa-Lobos, Piston, Sibelius, Poulenc, Busoni, Milhaud, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Hindemith, Roussel, Shostakovich, Vaughan Williams, and Ibert. Stravinsky alone wrote seven works scored for winds between 1916 and 1924. These were the Duet for Two Bassoons, The Soldier's Tale, Rag Time, Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo, Symphonies of Wind Instruments, Octet for Wind Instruments, and Concerto for Piano and Winds. While most of these works were written for small ensembles, nevertheless, composers with varied backgrounds were showing interest in wind composition. But despite the interest of composers, the band profession as a whole failed to capitalize on this opportunity (one notable exception was the competition for original band works begun by Edwin Franko Goldman in 1920).3 While a fair amount of interest was being shown by composers for the orchestral wind section, a number of original works for band or works transcribed by the composer for band were also being composed. During the first three decades of the 20th century these works included:

In 1929, the American Bandmasters Association was formed, with Sousa elected first honorary life president. From the ABA, efforts began to spread throughout the country (largely beginning at the University of Illinois) to standardize instrumentation, rehearsal techniques, and performance practices, and to encourage new repertoire. This atmosphere soon became the training ground for future directors.4 Also through the efforts of the ABA and influential conductors such as E. F. Goldman, the push for original band literature began. A few established composers such as Henry Cowell (Shoonthree, 1940), Gustav Holst (Hammersmith, 1930), Percy Grainger (Lincolnshire Posey, 1937), and Ottorino Resphigi (Huntingtower Ballad, 1932) responded to the need, but original concert works by American composers were still uncommon. - Back to Top -REPERTOIRE OF THE EARLY 1940sThe years during World War II saw a new wave of interest in composition for winds. One can only conjecture as to the reasons, outside of the obvious emphasis military bands enjoyed during this period. Some of the better-known composers and compositions include:

Despite the increasing interest in wind composition, the potential for new repertoire was not yet completely realized. David Whitwell notices in reviewing Prescott and Chidester's Getting Better Results with School Bands, a book published in 1938 that passed through ten successive printings, that the seventeen programs suggested for mature student bands were 85% transcriptions. Whitwell observed the same trend in R. F. Goldman's The Band's Music, also published in 1938. Although the first portion of the book contains an extensive list of original band music, the list of suggested repertoire found later in the book contains eight hundred works, more than 88% of which are transcriptions. Consequently, even though composers were showing greater interest in composing for winds in general, and bands specifically, over one hundred fifty major orchestral works were transcribed for band.5 - Back to Top -REPERTOIRE OF THE 1940s AND 1950s: AMERICAN COMPOSERS MAKE THEIR MARKAlthough original compositions were not as prevalent as one might have hoped, the band medium was gradually developing original repertoire, and American composers were showing particular interest. The next ten to twelve years would reflect ever-increasing interest of American composers in band compositions:

Even with the advent of new literature, the overwhelming use of transcriptions was still common. In 1956 The Instrumentalist began a series entitled "The Best in Band Music". In 1958 it compiled the results of the thirty-one contributors to the column. There were, in all, 118 titles that were suggested by at least three conductors. More than 66% of the titles were transcriptions, although those selections receiving the most notice were almost without exception original band works.6 - Back to Top -REPERTOIRE OF THE 1960sAmong the number of works composed in the 1960s are:

- Back to Top -REPERTOIRE OF THE 1970sBy the middle 1970s the balance between original literature and transcriptions began to tip the other way. By comparing numbers of original and transcribed works performed at the Midwest National Band and Orchestra Clinic and the College Band Directors National Association conventions, James Westbrook determined that only 27% of the compositions performed were transcriptions.7 At the present, an increasingly large amount of literature is being composed for the band medium. Admittedly, much of the new literature will not stand the test of time. But this tends to be consistent with all genres of music from any given period of music history. In trying to approach the status of the orchestral medium the band has often been frustrated by literature which is shorter in length and lighter in content. Many of the established Americans who wrote original works for band since World War II have written substantially more literature for orchestra. While giving the band repertoire works of higher quality, some of these composers still have not always approached band composition with the same energy and musical commitment with which they approached other mediums. For instance, Barber's Commando March - albeit a very fine march - will never sustain the notoriety of his Violin Concerto. The good news is that there were many others who accepted the challenge and provided works of length and breadth, such as the symphonies by Gould, Persichetti, and Giannini, La Fiesta Mexicana by H. Owen Reed, and Lincolnshire Posy by Grainger. As the amount of available repertoire grew, new works from the 1970s included:

- Back to Top -REPERTOIRE OF THE 1980sWorks written in the 1980s include:

- Back to Top -REPERTOIRE OF THE 1990sSelections for the 1990s include:

- Back to Top -CONCLUSIONThe quality and sophistication of wind band music in the last several decades has grown exponentially. Thick scoring and over-doubling are not as prevalent as in times past. The percussion section has at times held a position bordering on parity with the woodwinds and brass. The palette of tonal color rising from the percussion section is enormous, with the addition of unconventional objects such as brake drums, and a variety of ethnic drums and instruments. The mallet instruments have become an integral part of band scoring, as has the piano. It is not uncommon to see harp and celeste scored in band music. Singing from the ensemble is common, as well as variety of aleatoric practices. The manner in which composers viewed the wind band was forever changed with the writing of works such as Husa's Music for Prague 1968, and especially Schwantner's and the mountains rising nowhere... Schwantner's use of motivic development, piano, aleatoric effects, and an enormous percussion section utilizing innovative effects such as a water gong were revolutionary. The commitment from contemporary composers to write for the wind band has been most credible. More often than not in the past it was deemed fortunate to extract one or two works for band from major composers. Today it is exciting to realize that when one hears a performance by a major symphony orchestra of a work by Frank Ticheli, one can count numerous compositions of high merit written for the wind band by the same composer as well. Due to commitments from commissioning projects, grants and composition contests, the flow of new compositions for the wind band by talented, insightful composers has grown exponentially. Composers are increasingly aware that new compositions for band tend to enjoy more performances than those for orchestra. The good news concerning the ongoing renaissance of new band literature is that there is more music being written than can be played by any one ensemble. This plethora of new literature has finally made it possible to create a standard repertoire of great music for bands. The 21st century holds the challenge for proponents of the wind band to continue to support the music endeavors of school and professional ensembles as well as to foster the creation of new literature from the most capable composers available. - Back to Top -

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||