5

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Among all the fine arts, music is the one which exercises the greatest influence on the passions, and it is the one which legislators should most encourage. When the peasants stormed the Bastille on July 14, 1789, the course of French history was unalterably changed. In time the monarchy and aristocracy were destroyed, the church lost its political status, and the hope of liberty knocked at the door of the common man throughout Europe until the time of Napoleon's coronation. Led by Robespierre, the most militant segment of the revolution searched for an emotional catalyst to rally the commoners known as the "third estate" into a feeling of nationalistic pride. Music has often been a catalyst for stirring the emotions and arousing sentiment during times of revolution, and France was certainly not the exception. The ruling bourgeoisie needed something to affect the common people who congregated in outdoor mass assemblies. The wind band became vital to the effort, and as a result, went through a metamorphosis that proved to be the dawn of the modern concert band. - Back to Top -BAND MUSIC OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONThe Paris ConservatoryIt was during this period of French history that the famous Paris Conservatory was established. Sarrette's limited funds could not sustain the Corps de Music de la Garde Nationale indefinitely. So to provide instruction on the various instruments and help the band to perpetuate itself, he secured the establishment of a free municipal school, the Ecole gratuite de Musique de la Gard Nationale Parisienne, founded on June 9, 1792 and funded by the city of Paris. One hundred twenty students, sons of Guard members of age ten to twenty, received free music instruction on wind instruments by members of Sarratte's Guard band. The school was sanctioned by the Constitutional Assembly, and became officially known as the Conservatoire de musique (or Paris Conservatory), in 1795 although classes did not begin until a year later.1In September 1789 Bernard Sarrette, a captain in the National Guard, formed a band of forty-five players for the purpose of performing at civic festivals and demonstrations. A band was the logical choice for outside occasions, due to the sheer volume of sound required and the intonation problems string players might encounter. Sarrette was not a musician, so his contribution to this endeavor was mainly administrative. Francois-Joseph Gossec, a leading French symphonic composer, assisted by his seventeen-year-old student, Charles Simon Catel, undertook the musical directorship of the Corps De Musique de la Garde Nationale. It was their responsibility to direct the band and compose music deemed appropriate for special occasions. The sheer size of the band was revolutionary in itself, being over five times the size of the wind octet which was still the standard size in the military establishments and courts throughout the rest of Europe. By the end of 1789 the 45-member band grew to 78 members, only to be reduced to 54 in 1792. 2 piccolos

1st, 2nd B-flat clarinets 2 horns in F 2 trumpets 2 bassoons bass trombone serpent timpani Instrumentation for

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sunday July 26 at 11:30 A.M. Concert Hall rue Vivienne Dress Rehearsal of the Military Symphony Composed by M. Berlioz For the Funeral Ceremony of July 28 H. Berlioz This card will admit two. Funeral March, Hymn of Farewell, Apotheosis.3 |

"Hymn of Farewell" was the original title of Oraison Funèbre.

The enthusiasm from this event sparked the promoters of the Concerts Vivienne to arrange two repeat performances. These performances prompted accolades from no less than the leading French conductor François Antoine Habaneck and the composer Richard Wagner. Wagner, not yet a household name and struggling to provide an income, was a correspondent for the Dresden Abend-Zeitung. Concerning the performance, he wrote:

I am inclined to rank this composition above all Berlioz' other ones; it is great from the first note to the last. It sustains a noble patriotic emotion which rises from lament to the topmost height of apotheosis. When I further take into account the service rendered by Berlioz in his altogether noble treatment of the military wind band...I must say with delight that I am convinced this "Symphonie" will last and exalt the hearts of men as long as there lives a nation called France.4

| piccolo in D-flat | (4) | bass trombone | (1) | |||

| flute in E-flat | (5) | (non obligé) | ||||

| oboe | (5) | ophicléide in C | I | (3) | ||

| clarinet in E-flat | (5) | ophicléide in B-flat | II | (3) | ||

| clarinet in B-flat | I | (14) | side drum | I | (4) | |

| II | (12) | II | (4) | |||

| bass clarinet in B-flat | (2) | timpani (1 pair) | ||||

| bassoon | I | (4) | cymbals (3 pair) | |||

| II | (4) | bass drum | (1) | |||

| contrabassoon | (1) | gong | (1) | |||

| (non obligé) | Turkish crescent | (1) | ||||

| horn in F | I,II | (4) | chorus (non obligé) | (200) | ||

| horn in A-flat | III,IV | (4) | violin (non obligé) | I | (20) | |

| horn in C | V,VI | (4) | II | (20) | ||

| trumpet in F | I,II | (4) | viola (non obligé) | (15) | ||

| trumpet in C | III,IV | (4) | cello (non obligé) | (15) | ||

| cornet á pistons in A-flat | I,II | (4) | bass (non obligé) | (10) | ||

| trombone | ||||||

| (alto or tenor) | I | (4) | ||||

| (tenor) | II | (3) | ||||

| (tenor) | III | (3) | ||||

Instrumentation for Berlioz' |

||||||

According to the Revue et Gazette Musicale of August 6, 1840, there were a total of 207 participants at the first performance. The symphony was again performed at the Opera on November 1, 1840 with 450 musicians. Optional string parts were added for a February 1842 performance, with choral parts added to the last movement soon afterwards. The final version was heard in Brussels on September 26 of the same year with a choral text written by Antony Deschamps and the melody to the Apotheosis adapted for voices. Throughout Berlioz' lifetime the number of performers used varied widely, from 130 instrumentalists in the Conservatoire on November 19, 1843 to a chorus and orchestra of 1800 in the Hippodrome in Paris on July 24, 1846. Despite the diversity of performance areas and personnel, he held very decided opinions of the optimum performance atmosphere. Concerning open-air performances, he was not overly enthusiastic: Berlioz said, "Open-air music is a chimera; 150 musicians in a closed building produce more effect than 1800 in the Hippodrome scattering their harmonies to the winds."5

The instrumentation changed as the music was altered through the years, so a variety of suggested instrumentations exist. The instrumentation as provided here is from the autograph score.6 Earlier French examples of band music pale in comparison. In later years, Berlioz abandoned the outdoor performances and promoted the second and third movements. He referred to the third as his "indestructable war horse", and eventually arranged it for chorus, vocal solo, and piano accompaniment. Even when not performed strictly as a band piece, the winds remained the dominant color, as evidenced by the additional wind players requested whenever strings were added.7

This symphony is among Berlioz' least known works, probably due, in part, to the fact that it is originally a band piece. Although some critics have panned it as inferior to Berlioz's other works, it also has its defenders. Jacues Barzun, author of Berlioz and the Romantic Century, writes "he fully achieved his goal of blending grandeur with nobility and simplicity with elevation..."8 Virgil Thomson, writing for the New York Herald Tribune, wrote the following on the occasion of the symphony's American premiere by the Goldman Band:

The sound of the thing is Berlioz at his best. No other composer has ever made a band sound so dark, so rich, so nobly somber. That sound is not only a beautiful and wondrous thing in itself; it is also part of the work's expressivity. It is everything that could possibly be meant by the adjectives funereal and triumphal. The tunes are noble, too; not one is lacking in sobriety. The whole composition is at once simple, serious and utterly sumptuous. It is as impersonal as a public building and at the same time deeply touching. The touching quality does not come from any private emotional assertion of the composer and still less from any calculated attempt on his part to provoke our tears. It comes, believe it or not, from the perfect taste of his stylistic conception...the military combined with a memorial subject call forth a richness of utterance and an impeccability of tone that make his "Grand Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale" one of the great ceremonial pieces of all time.9

- Back to Top -

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

oboe (2)

clarinet in F (2)

clarinet in C (2)

bassett horn (2)

bassoon (2)

horn in E (2)

horn in C (2)

trumpet in C (2)

alto trombone

tenor trombone

bass trombone

contrabassoon

bass horn

Instrumentation for

Overture for Wind Band, op. 24

by Felix Mendelssohn

Another significant work of the early 19th century came from the pen of Felix Mendelssohn during his fifteenth year. In the summer of 1824, on holiday in northern Germany at the spa of Bad Doberan, Mendelssohn enjoyed the music of a small resident ensemble. He quickly seized the opportunity to write Notturno, which eventually became known as the Overture for Wind Band, Op. 24. The original music was written in Harmoniemusik style of 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, and 2 horns, with the addition of one flute, one trumpet, and the "English basshorn", which combines elements of the serpent and ophicleide. In 1838 he rewrote the score for large ensemble, which is the instrumentation found in his complete works, the Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy: Werke. While not demanding the virtuosity of Mendelssohn's more famous works, it is still an engaging piece that has surfaced in a variety of editions throughout the years, migrating from the European continent to the United States in the 19th century to the Gilmore Band Library (No.145) and Carl Fischer's U.S. Military Band Journal (No. 179).10

Also found in the Werke is Mendelssohn's Trauer-Marsch for band, composed May 8, 1836 and dedicated to Norbert Burgmüller who had died the previous day. Burgmüller was a young composer of exceptional promise who died at the age of twenty-six. David Whitwell speculates that the piece was indeed begun much earlier, perhaps as the result of the death of Mendelssohn's father, and that the Burgmüller service was simply the first opportunity to perform the work.11

- Back to Top -

WILHELM WIEPRECHT

Berlioz in Germany

Berlioz' trip to Germany was a rewarding opportunity for him, as he was not always treated in France with the respect that was probably due him. Perhaps his greatest enthusiasm on the tour was reserved for a semi-private performance the Crown Prince of Prussia had scheduled for him to hear and study the musical troops. Upon arrival at the matinee performance, Berlioz was astonished to see no musicians present, when presently he recognized the opening strains of his Francs-Juges Overture emanating from behind the curtain of the largest room in the palace. There, much to his pleasure, were three hundred twenty military bandsmen performing with "marvelous exactness" and "furious fire". He praised the facility of the clarinets and expressed his fascination and enthusiasm for the bass tuba, an instrument he found to be far superior to the opheclide.2Arguably the most influential person behind the evolution of European military bands in the 19th century was Wilhelm Wieprecht. Born in 1802, Wieprecht's musical heritage included a father, grandfather, and four uncles who were all professional musicians. He began his studies on clarinet and violin. Later he studied trombone on his own, and, despite being self taught, reached a level of proficiency that rivaled the leading trombonist in Liepzig. He apprenticed to the music guild at the age of fourteen, receiving his Journeyman's Certificate from the guild in 1820. Although his father expected Wieprecht to take his place in the civic wind band of Aschersleben, in Thuringen, he instead spent nine months at the court in Dresden, followed by a two-year stint in Leipzig, before settling in Berlin as a chamber musician of the court.

Prussian Military Bands

While in Berlin, events occurred which determined the direction of his career for the remainder of his life. Upon a chance hearing, Wieprecht was enthralled with an infantry band's rendition of the overture to Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro. From that moment he resolved to devote himself to military music.12 Since the age of the great repertory orchestras was just beginning, the infantry band's performance very likely rivaled that of the opera house orchestras most people were accustomed to hearing.

Berlioz spoke highly of their ability during his German tour of 1842-43. In a letter to Monsieur Desmarest, a cellist at the Paris Conservatoire, he spoke of the prolific appearances of military bands at all times of day throughout the city of Berlin. Berlioz was impressed that Wieprecht had at his disposal upwards of six hundred musicians. He explained that the musicians were:

all good readers, all well up in the mechanism of their instruments, playing in tune, and favoured by nature with indefatigable lungs and lips of leather. Hence the extreme facility with which the trumpets, horns, and cornets give those high notes unattainable by our artists. They are regiments of musicians, rather than musicians of regiments.

- Back to Top -

Toward Consistent Instrumentation

Wieprecht lived at a most opportune time. First, money was being earmarked for the upgrade of military bands. Second, this was period of innovation for a number of instruments, from the invention of the valve for brass instruments to the refinement of mechanisms for various woodwind instruments. However, with all this unsettling change there was no unified system of instrumentation. Wieprecht was a man of vision and energy, and creating such a system became his greatest legacy.

Wieprecht initiated this new direction by composing six regimental marches for the Guard Dragoon Regiment, under a Major von Barner. This was a group absent of woodwind players, in contrast to the old Harmoniemusik system still popular in other military outlays. Because of the severe melodic limitations imposed by the group's instrumentation (natural trumpets in G, F, and C, and trombones) he persuaded the Major to buy valved instruments, which, up until this time, were not used in Berlin cavalry units. By adding seven more players to the original thirteen of the band, Wieprecht realized a group that could not be hindered melodically or harmonically.

The success of this endeavor soon brought an order from King Friedrich Wilhelm III for Wieprecht to re-instrument the Guard Regiment in Potsdam. Soon the king engaged him to instruct the trumpets of the regiment, so four days out of each month, Wieprecht went to Potsdam to work with the entire music corps of Berlin and Charlittenburg. In 1833 he replaced the high trumpets, keyed trumpets, and alto trumpets with suitable cornets, which provided a more lyrical sound with less edginess.13

- Back to Top -

Massed Concerts and Additional Reforms

In 1838, upon the retirement of Abraham Schneider, Wieprecht became the overall director of the Guard music in Berlin. Presently, the King charged him with organizing a great Festmusik for the state visit of Nicholaus of Russia. This and other mass concerts would make Wieprecht a well-known person in Berlin. The concert was held in an open square before the Berliner Schloss with sixteen cavalry and sixteen infantry bands totaling more than 1000 winds and 200 percussionists performing. The program consisted of the following:

-

Overture to Rienzi by Wagner, played by the full ensemble.

-

"Chorus" and "March" from Conradin by Hillear, performed by the bands of the foot troops.

-

"Hallelujah" from Messiah by Handel, performed by the infantry bands.

-

March by Möllendorf, performed by the cavalry bands.

-

"Coronation March" from The Prophet by Meyerbeer, performed by the full ensemble.

-

The Dessauer, Hohenfriedberger, and Coburger marches, performed by the full ensemble.

In 1843 an event occurred which brought home the need for standard instrumentation in a most awkward way. Wieprecht had been given the opportunity to organize another massive concert, this time in Lüneburg. More than thirteen hundred non-Prussian musicians representing military bands quartered in Hannover, Holstein, Läuenburg, Oldenburg, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Braunschweig, Humburg, Lübeck, and Bremen gathered to rehearse and perform. Due to their instrumental diversity, he had to write out seventeen different versions of the infantry parts and nine different versions of the cavalry parts!14

TIn 1845 Wieprecht decided to tackle the problem directly by writing a series of articles to generate support for standardization of instrumentation. He called for bands of twenty-one parts, with doubling as needed for optimum balance and texture. These he grouped into three registers, further balanced into an "acoustic pyramid". Below are the instrumentations for both guard and line infantry bands.

| Instrumentation for: | Guard Infantry | Line Infantry |

|---|---|---|

| Piercing register, to be played lightly | ||

| flutes, large and small | 2 | 1 |

| clarinets in A-flat or G | 2 | 2 |

| clarinets in E-flat or D | 2 | 2 |

| clarinets in B-flat or A | 8 | 6 |

| oboes in E-flat or D | 2 | 2 |

| bassoons | 2 | 2 |

| batyphons | 2 | 2 |

| Middle register, to be played stronger | ||

| cornets in B-flat or A | 2 | 1 |

| cornets in E-flat or D | 2 | 1 |

| tenorhorns in B-flat or A | 2 | 1 |

| bass horns (Baryton) in B-flat or A | 1 | 1 |

| bass horns in F or E-flat | 2 | 1 |

| Low register, to be played very strong | ||

| trumpets in E-flat or D | 4 | 4 |

| trombones in B-flat or A | 2 | 2 |

| bass trombones in F or E-flat | 2 | 2 |

| bass tuba in F or E-flat | 2 | 2 |

| triangle | 1 | 1 |

| cymbals | 1 | 1 |

| small drum | 2 | 1 |

| bass drum | 1 | 1 |

| Schellenbaum | 1 | 1 |

| Conductor | 1 | 1 |

His concept was similar to the pyramid approach advocated by Frances McBeth in his Band Performance Guide where the highest pitched voices do not play as loud as the low voices, thus creating a more acceptable, balanced sound.

In time his ideas took hold, and by mid-century large concert bands of fifty to sixty musicians became common in Prussia. For instance, in 1848 a Prussian infantry band consisted of the following:

| 8 to 10 clarinets given the melody, including 2 small clarinets |

| 8 to 10 clarinets serving as accompaniment |

| 2 first oboes |

| 2 second oboes |

| 2 basset horns |

| 2 flutes or piccolo |

| 2 first bassoons |

| 2 second bassoons |

| 4 horns |

| 4 trumpets, 2 "ordinaires", 2 with valves |

| 4 trombones (ATBB) |

| serpent |

| contrabassoon (often two) |

| tuba, bombardon, or bass horn |

| 1 or 2 small drums |

| cymbals |

| triangle16 |

Later, Wieprecht further refined the instrumentation by replacing keyed bugles (Kenthorns) with valved cornets. In 1860 he was given the responsibility of creating bands for thirty-four new infantry and ten new cavalry regiments. This afforded a great opportunity to revise his instrumentation concepts into one plan for all the bands--cavalry, Jäger, artillery, or infantry. His idea was for publishers to score music in accordance with his plan so that the same piece could be purchased and used by any of the types of bands.

| Unified Instrumentation System of 1860 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavalry | Artillery | Jäger | Infantry | |

| cornettino | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| soprano cornet | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| alto cornet | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| tenorhorn | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| baritone-tuba | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| bass tuba | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| trumpet | 8 | 12 | 3 | 4 |

| horn | 4 | 4 | ||

| flute | 2 | |||

| oboe | 2 | |||

| clarinet in A-flat | 1 | |||

| clarinet in E-flat | 2 | |||

| clarinet in B-flat | 8 | |||

| bassoon | 2 | |||

| contrabassoon | 2 | |||

| trombone | 4 | |||

| cymbals | 1 | |||

| small drum | 2 | |||

| large drum | 1 | |||

| halbmondträger | 1 | |||

| Total: | 21 | 39 | 21 | 4717 |

Wieprecht's stellar career reached its apex in 1867 at the World Competition in Paris. Here his Prussian Imperial Guard Band took first place honors in competition representing bands from nine countries. Wieprecht was also known for composing a number of works for military band, as well as penning numerous arrangements of other composer's music.

- Back to Top -

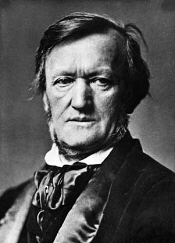

RICHARD WAGNER

Even as Wieprecht used the innovations of instrument development and design to transform the Prussian military bands into a more or less modern form, the same benefits were also realized in the orchestra. The instigation for reform and innovation came first through Berlioz, followed closely by Richard Wagner. Not only was he a revolutionary in music drama, but in orchestration as well. One fundamental change was the doubling of size of the wind section in the orchestra, including the invention of the Wagner tuba that was designed to fill in the harmonic gap between the French horn and the tuba. Another change was in the color of sound that he achieved from the orchestra. His composition technique often created a homogeneous sound in which the harmonic structure was found complete in all three sections--strings, woodwinds, and brass. This explains the relative ease in transcribing his music for wind band--much of the task is already done.

Early Works

| flute I flute II oboe I oboe II clarinet in B-flat I clarinet in B-flat II bassoon I bassoon II horn in F I horn in F II horn in low B-flat I horn in low B-flat II trumpet in F I trumpet in F II alto trombone tenor trombone bass trombone bass tuba muted snare drums |

(3) (2) (4) (3) (10) (10) (5) (5) (4) (4) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (4) (6) |

Instrumentation for Trauersinfonie |

|

Wagner wrote two works for winds early in his career that are somewhat obscure. Weihegruss was written for orchestral brass (4,3,3,1) and male chorus, and performed as ceremonial music for the unveiling of the Statue of King Friedrich August I, on June 7, 1843. The second was the Greeting to Friedrich August II of Saxony, first performed on August 12, 1844, upon the return of the King from a visit to England. The original manuscript for this work, written for military band and male chorus, is in the Houghton Library at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wagner perhaps had more than a passing interest in the royalty he so honored, since his mother was the illegitimate daughter of Prince Friedrich Ferdinand Constantin, brother of Grand Duke Karl August of Weimar, making Richard a somewhat distant blood relation.

Trauersinfonie

The more familiar Trauersinfonie, based on themes from Weber's Euryanthe, was first performed on December 14, 1844. This music was written to aid the torchlight procession that carried the ashes of Carl Maria von Weber from the Dresden train station to their final resting place, some eighteen years after his death in London. Wagner's surname until the age of fourteen was Geyer, and Weber had visited the Geyer household many times, as well as joining them on family picnics. Wagner had conducted Weber's music a number of times prior to 1844 and no doubt considered himself the heir to the German opera tradition to which Weber contributed so richly. This is solemn, yet contemplative music of which Frederick Fennell says "no apology need be made for this music." Indeed the entire mood of the music provides contemporary audiences a stylistic contrast to band music as a whole.

- Back to Top -

Huldingungsmarsch

Wagner wrote the Huldigungsmarsch in 1864. The third written score has the inscription "For the Nineteenth Birthday of His Majesty King Ludwig II by Richard Wagner". Wagner was deeply indebted to Ludwig, who pulled Wagner out of a crippling debt and financed the first production of the Ring of the Nibelungen. This was the same Ludwig who was declared insane in 1886 and removed from the throne before he completely depleted the state's coffers on extravagant projects such as the picturesque Neuschwanstein castle, located in the Bavarian Alps.

Kaisermarsch

There are some that speculate that the Kaisermarsch of 1871 was originally scored for band. However, the only score from Wagner's hand is for orchestra. Some claim that Wieprecht, who was the Kaiser's bandmaster scored the work, but Cosima Wagner tells us that Richard withheld his approval when Wieprecht requested permission to transcribe the work. So, caution suggests that this was not an original band work.

Twenty years separate the Trauersinfonie and the Huldigungsmarsch, and with that comes the maturation and evolution of the technique of the composer. Trauersinfonie paralleled the appearance of Rienzi (1842), The Flying Dutchman (1843) and Tannhäuser (1845), while the march came at a time when a more mature Wagner had completed Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, and much of Seigfried, Die Meistersinger, and Tristan und Isolde.

- Back to Top -

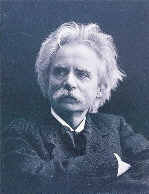

EDVARD GRIEG

| piccolo in E-flat flute in E-flat clarinet in E-flat clarinet in B-flat oboe cornet in B-flat trumpet in E-flat horn in E-flat bassoon alto trombone tenor trombone tuba side drum bass drum |

(2) (2) (2) (2) (2) (2) (2) (2) (2) |

Instrumentation for |

Rikard Nordraak wrote the Norwegian national anthem and had devoted his life to developing a true Norwegian style of composition before his untimely death in 1866 at the age of 24. He claimed an advocate and close friend in Edvard Grieg who wrote the Funeral March in Memory of Rikard Nordraak in tribute. Initially written for piano solo, Grieg eventually wrote versions for brass band and military band. It is not clear when the military band version was scored--it could have been as early as 1867, but no later than 1891. C. F. Peters published a military band version in 1899. This piece is in B-flat minor, and not in G minor, as some titles have indicated. The Funeral March was a personal favorite of Grieg, who carried it with him on concert tours and also conducted it personally on occasion. Grieg was fortunate to receive a hearing of his music with the celebrated composer Franz Liszt, at which time the march, the G Major Violin Sonata, and the volume including "Cradle Song," were among the pieces presented.18 Indeed, his burial request included the following:

I wish to be buried in my native town, and I desire that at the interment my Nordraak funeral march--which I always carry with me when I travel--be played as beautifully as possible.

Although mostly neglected, this is nevertheless a quality piece, noble and contemplative, and championed by no less than Richard Franco Goldman and released by Frederick Fennell on compact disc. It demonstrates Grieg's style as a mature melodist and harmonist. Goldman endorses the Trauermarsch enthusiastically as "one of the grandest works for band", containing "great intensity, marvelous color, and immense pathos.19 It is ironic that a work so highly esteemed by the composer himself has suffered neglect, especially in light of the need for more literature from this period of wind band history.

- Back to Top -

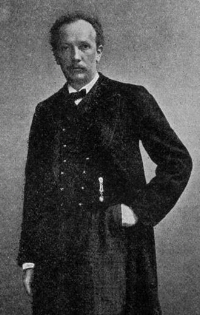

RICHARD STRAUSS

As 19th century Romanticism reached its twilight years two composers provided the greatest influence on the German School--Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. While Mahler would die at the height of his career in 1911, Strauss lived well in to the middle of the 20th century. He composed actively up until his death, but had long since outlived any reputation for innovative thinking, finishing in a style similar to that with which he began.

Serenade in E-flat

Strauss' first composition of notoriety was written when he was approximately eighteen. The Serenade for Wind Instruments, Op. 7 showed maturity in technique and style that, in turn, brought him a measure of respect from the music world that would endure for the next sixty-five years. The instrumentation is 2fl., 2ob., 2cl., 2bsn., and 4 horns with a contrabassoon for added bass support. Writing for winds should have been no problem for Strauss as his father was a professional horn player in the Munich Court Orchestra and professor at the Royal School of Music. The Serenade represented a major step towards more successful works such as the famous tone poems to follow, though in 1909 Strauss himself would give it no more credit than simply a "respectable work of a music student." The premiere was given on November 27, 1882 under the baton of Franz Wüllner who later would conduct first performances of Till Eulenspiegel and Don Quixote.20

Suite in B-flat

During the following year the Serenade received several performances, but it was not until it came to the attention of Hans von Bülow that Strauss began to receive significant notoriety. Von Bülow not only placed it in his regular repertoire but also suggested that Strauss compose another work for the same combination. Strauss gladly set to work and already had the opening Allegretto and a Romanze finished, only to find out that von Bülow had in mind a form befitting a Suite. So Strauss met the demand by finishing with a Gavotte and an Introduction and Fugue as the final two movements. Some time later von Bülow provided Strauss the opportunity to conduct the Suite in B-flat, Op. 4 at an afternoon concert. The Meiningen Orchestra was on tour, so Bülow refused Strauss any rehearsal time. Though he had never picked up a baton, the somewhat terrified Strauss elected to not pass on the opportunity, commenting: "I conducted my piece in a state of slight coma; I can only remember today that I made no blunders." Thus launched a second career as a conductor since von Bülow made him assistant conductor within the month. It is confusing that the Suite is listed as op. 4 while the earlier Serenade is op.7, but this is due to the fact that the Suite was not published until 1911 and was given an opus number originally intended for an overture that was never published.21 Many years later he would return to the winds as a composition medium.

- Back to Top -

Fanfare der Stadt Wien

In 1942 Europe was in the throes of war, and Strauss and his wife Pauline were frustrated with sickness and health problems connected with advancing age. Accolades continued to come his way as a celebrated composer, as he received the Beethoven Prize from the city of Vienna. As a return gesture he penned a stirring Festmusik for the Vienna Trompeterchor supported by trombones, tubas, and timpani. Strauss conducted the work himself in April of 1943, and being personally pleased with its success, he honored a request by the Trompeterchor to shorten the somewhat formidable piece of fifteen minutes' length to something that could more easily be put into their regular repertoire.22 The resulting Fanfare der Stadt Wien is one of the most effective pieces in the brass wind repertoire.

The Invalid and Cheerful Workshops

A wealth of memories embraced Strauss as he fondly recalled the earlier wind works that served as a catalyst in launching his career as both composer and conductor. He had for a long time felt that he had miscalculated the balance between horn and woodwinds in the earlier attempts and wanted to explore the concept again--this while acknowledging that he clearly had nothing new of importance to say. By February 21 he had finished the Romanze and Minuet, in which he used only two horns but added a basset horn and bass clarinet. He then tackled the outer movements in which he restored the 3rd and 4th horns and added a fifth clarinet in C. The clarinet in C was to help reinforce the upper register without the shrill qualities of the E-flat clarinet, a technique that he had used in his later operas. He affectionately referred to this new endeavor as: I Sonatine für Blasinstrumente Aus der Werkstatt eines Invaliden ("from the workshop of an invalid"). He arranged for the first performance to be given by the Tonkünstlerverein du Dresden, where his Serenade, op. 7 originally premiered. The performance did not take place until June 18, 1944.

The Symphonie für Bläser was completed by the end of June 1945, soon after the European armistice. More in the style of the Sonatina, it nevertheless received the title of symphony at publication, no doubt because of its nearly 40 minutes of length. It was subtitled Frölich Werkstatt or "Cheerful Workshop" and dedicated to "the spirit of the immortal Mozart at the end of a life of thankfulness"--all this despite the desperate circumstances in which Strauss and his family found themselves. His assets were frozen and he was under scrutiny for supposed collaboration with the Third Reich, so under the encouragement of friends, he and his family took refuge in Switzerland for the next four years.23

- Back to Top -

ANTONÍN DVORÁK

When Dvorák penned his Serenade, Op.44 in 1878, he was enjoying a time of great success. Scored for 0222,cbsn/3000 with added cello and doublebass, it hearkens back to the qualities of Classical chamber music with the added touch of his melodic genious. This is cheerful music, with genuine qualities that make it very easy to listen to. No less than Johannes Brahms admired this work and recommended it to his publisher Simrock and to his friends Joseph Joachim and Theodore Billroth. In writing to his old friend Billroth he said:

I very much recommend to you a Serenade of Dvorák for wind instruments which also has appeared for four-hand piano playing and is one of the best that has been composed by himself. It ought to give you great pleasure.24

Dvorák was indebted to Brahms for championing his cause on numerous occasions.

- Back to Top -

Charles Gounod

A complement to the Dvorák Serenade is the Petite Symphonie in B-flat by Charles Gounod, written during his 69th year. Gounod was a most successful composer of opera in the mid-nineteenth century, and his gift of melody is not lost in this engaging work for winds. The Petite Symphonie is scored for 1222/2000. It was written for the Société de Musique de chambre pour instruments à vent, whose leader was the flautist and conductor Paul Taffenel.

- Back to Top -

Other Works

There were other works for winds written in Europe during the nineteenth century that may be of interest to the reader. The Notturno in C, op.34 by Spohr (1815) is a piece in six movements and incorporates Turkish influences in the percussion. Marches by Gaetano Donizetti (1835) and by Gioacchino Rossini (1851) are the result of commissions by Donizetti's brother, Giuseppe, who was in charge of Turkish military bands under the Sultan Abdul Medjid beginning in 1832. The Overture in C by Louis Jadin and the Overture in F by Hyacinth Jadin were written during the years of the French Revolution, while the Three Grand Military Marches by Hummel date from c.1820. Other marches include the Apollo March and March in E-flat by Anton Bruckner, March Orient et Occident by Camille Saint Saëns, and Marche Militaire by Peter Tchaikowsky.

- Back to Top -

- Next Chapter -

- Table of Contents -

ENDNOTES

1Boris Schwarz, French Instrumental Music Between the Revolutions (1789-1830) (New York: Da Capo Press, 1987), 10-12.

2David Whitwell, "Reicha's Commemoration Symphony for Band," Journal of Band Research 9:2 (Spring 1973): 36-37.

3Facsimile in Karlovicz, Souvenirs Inédits de Chopin (s.n.: A.R., n.d.), 419.

4Frank P. Byrne, album notes for Hector Berlioz, recording of The United States Marine Band, conducted by Col. John R. Bourgeois.

5Journal des Debats, July 29, 1846.

6New edition of The Complete Works of Hector Berlioz (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1967 (1986)) Vol. 19, p. .

7Complete works of Berlioz, Vol. 19, p. IX-X.

8Jacques Barzun, Berlioz and the Romantic Century Vol. I 3rd ed. rev. from first (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), 364.

9Richard Franco Goldman, The Wind Band: Its Literature and Technique (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc., 1961), 218.

10David F. Reed, "The Original Version of the Overture for Wind Band of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy," Journal of Band Research 18:1 (Fall 1982): 3-7.

11David Whitwell, A New History of Wind Music (Evanston, Illinois: The Instrumentalist Co., 1972): 27.

12Ibid., 31-32.

13Whitwell, 33-34.

14Ibid., 37.

15Ibid., 39-40.

16Ibid., 41.

17Ibid., 43.

18John Jay Hilfiger, "Edvard Grieg's Funeral March in Memory of Rikard Nordraak for Military Band," Journal of Band Research Vol. 24 No. 2 (Spring, 1989), 12-14.

19Goldman, 222.

20Norman Del Mar, Richard Strauss - A Critical Commentary on His Life Works Volume I (London: Chilton Book Company, 1962), 9-10.

21Ibid., Vol. I, 9-13.

22Ibid., Vol. III, 412-413.

23Ibid., 432.

24Hans Barkan, translator and editor, Johannes Brahms and Theodore Billroth - Letters from a Musical Friendship. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1957), p. 80.

SIDEBAR NOTES

1Schwartz, p. 13.

2Ernest Newman, Memoirs of Hector Berlioz from 1803 to 1865 comprising his travels in Germany, Italy, Russia, and England (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1932), 325-326.

PICTURE CREDITS

1Episode of the Belgian Revolution, 1830, by Egide Charles Gustave Wappers, 1834. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Wappers_belgian_revolution.jpg.

2Excerpt from portrait of François-Joseph Gossec by Antoine Vestier. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Gossec-portrait.jpg.

3Engraved portrait of Anton Reicha by M.F. Dien, 1815. Used by permission.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Reicha.jpg.

4Portrait of Hector Berlioz by Emile Signol, 1831-1832. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Berliozpaint.gif.

5Photograph of the Place de la Bastille and the July Column, taken by Kaihsu Tai, 1999. Used by permission.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:PlaceBastille20040914.JPG.

6Watercolor portrait of Felix Mendolssohn Bartholdy by James Warren Childe, 1839. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Mendelssohn_Bartholdy.jpg.

7Photograph of Wilhelm Wieprect, photographer unknown. From R. Cadario, "Un genio musicale per i fiati", Unisono 18 (Sept. 30, 2002): 27. Used by permission of the Schweizer Blasmusikverband SBV.

Source: http://www.windband.ch/uploads/media/uso_18_01.pdf.

9Portrait of Wilhelm Friedrich III, King of Prussia, artist unknown. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:FWIII.jpg.

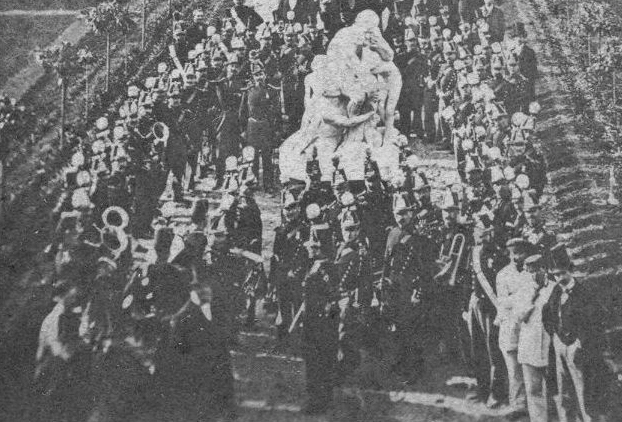

10Photograph of unidentified bands at the Paris Exposition, 1867, photographer unknown. From the web site The Internet Bandsman's Everything Within. Used by permission.

Source: http://www.satiche.org.uk/vinbbp/phot2266.jpg.

11Photograph of Richard Wagner, taken by Franz Hanfstaengl, 1871. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:RichardWagner.jpg.

12Photograph of Edvard Grieg, photographer unknown. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Edvard_Grieg.jpg.

13Photograph of Richard Strauss, photographer unknown, prior to 1918. From Modern Music and Musicians (New York: University Society, 1918). Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Richard_Strauss.jpg.

14Photograph of Richard Strauss, photographer unknown, 1940s? Public domain.

Source: http://people.unt.edu/~dmeek/Strauss5.jpg.

15Photograph of Antonín Dvorák, photographer unknown. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Dvorak.jpg.

16Photograph of Charles Gounod, photographer unknown. From Rupert Hughes, The Love Affairs of the Great Musicians, vol. II (Boston: L.C. Page, 1903). Used under Project Gutenberg license: "This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org."

Source: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11419/11419-h/11419-h.htm.

17Self-portrait of Louis (Ludwig) Spohr. Public domain.

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Spohr.jpg.